Rescue of Jane Johnson

By Celia Caust-Ellenbogen

Swarthmore College, Class of 2009. Quakers & Slavery Digitization Project Intern

Philadelphia, 1855

In 1855, the city of Philadelphia was divided on the question of slavery. On the one hand, it was the base of several outspoken anti-slavery organizations, largely driven by the city's resident population of Friends. On the other hand, it was also home to a contingent of pro-slavery sympathizers, a fact made all too obvious by the mob violence against the abolitionist "Temple of Free Speech," Pennsylvania Hall, in 1838. Pennsylvania was a free state bordered by slave states; it was a transitional space with an ambivalent population, where some escaped slaves settled but far more only passed through. Exact figures do not exist, but William Still recorded that the Vigilance Committee (of which he was Chairman) saw 60 fugitive slaves pass through Philadelphia in a single month in 1857 (Still 97).

The presence, temporary or permanent, of escaped slaves became an increasingly complex issue with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The new federal law, part of the Compromise of 1850, strengthened the 1793 fugitive slave law as a concession to slaveholders. It was now legal for law enforcement officers to conscript any citizen for assistance in securing an escaped slave; those who refused were liable to imprisonment and fines. At the same time, it became easier to allege a black was an escaped slave, and impossible for him to defend himself in court, resulting in the kidnapping into slavery of free blacks who had obtained their freedom quite legally.

Much to the slaveholders' chagrin, the 1850 act had the opposite of its intended effect. It rallied the anger of existing abolitionists, but moreover, it provoked a backlash amongst previously ambivalent northerners now faced with the prospect of being drafted to hunt down a fugitive slave. Abolitionists and northern states' rights advocates disavowed the federal slave law, placing authority in state "Personal Liberty Laws" instead. In 1842, Pennsylvania's personal liberty law had been declared unconstitutional by Roger B. Taney's Supreme Court (which would later rule on the landmark Dred Scott case in 1857); but Pennsylvania passed a modified version of its personal liberty law in 1847. It was under this 1847 law that Pennsylvania conductors of the Underground Railroad claimed the right to continue their activities. (Brandt 88)

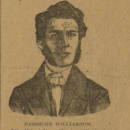

Amidst the confusion surrounding fugitive slaves' rights, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society maintained a Vigilance Committee that was charged with assisting runaway slaves in Philadelphia. In 1855, as the result of an 1852 reorganization, the acting subcommittee consisted of four men with William Still as chair (Brandt 27). Only one of the four was white: Passmore Williamson, 1822-1895. A birthright Friend, Williamson was disowned in 1848 for neglecting to attend meeting, but he nevertheless continued to live a Quaker lifestyle for the rest of his life.

Escape

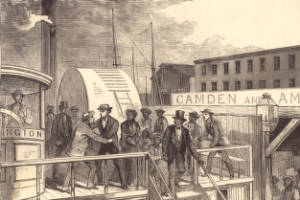

In July of 1855, John H. Wheeler, a North Carolina politician and the United States ambassador to Nicaragua, brought his slave Jane Johnson and her two children with him on a journey to South America. Although they would be travelling through free states--even stopping overnight in Philadelphia and New York--Wheeler apparently was not overly concerned that his slaves would attempt to escape. He planned to keep a close eye on his slaves, but he underestimated the will and resolve of Jane. While still in Philadelphia, she approached some free blacks and confided her desire to run away; someone sent a hurried message to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society; and just after Wheeler had settled with his slaves on a ferry to depart from Philadelphia, Passmore Williamson, William Still, and five colored dockworkers boarded the ship.

Passmore Williamson quickly located Johnson and explained to her that she was free. William Still later recalled his words: "You are entitled to your freedom according to the laws of Pennsylvania, having been brought into the State by your owner" (Still 88). Wheeler protested, but two of the colored dockworkers, John Ballard and William Curtis, held him back. Johnson exclaimed, "I am not free, but I want my freedom--ALWAYS wanted to be free!! but he holds me" (Still 89). William Still led Johnson and her children off the ferry and into a carriage, and that day, July 18, 1855, they were free.

Case of Passmore Williamson

A furious Wheeler petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus that would force Passmore Williamson, Johnson's "abductor," to produce her to the court. The writ was granted by Judge John K. Kane, who, disregarding William Still and the other five freedmen who assisted Johnson's escape, placed all responsibility with Williamson. "Of all the parties to the act of violence, he was the only white man, the only citizen, the only individual having recognized political rights, the only person whose social training could certainly interpret either his own duties or the rights of others under the constitution of the land" (Kane qtd. in Williamson, 12). When Williamson refused to comply, claiming (truthfully) that he had no knowledge of Johnson's whereabouts, he was held in contempt of court.

From July 27, 1855, Williamson spent over three months in Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia. As with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, however, the anti-abolitionists' excessive zeal backfired: the main result of Williamson's imprisonment was that it attracted support for his cause. "The opportunity seemed favorable for teaching abolitionists and negroes, that they had no right to interfere with a 'chivalrous southern gentleman,'" William Still later wrote of Wheeler's hubris; but Williamson's "resolute course was bringing floods of sympathy throughout the North" (Still 92, 93). It seemed that the longer Williamson endured imprisonment, the more respect he earned. "Passmore is very cheerful, & firm as a rock," Lucretia Mott recorded after visiting him in September (connect to primary source and full transcript.). In addition to Mott, he received a long string of distinguished visitors, including Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Supportive letters arrived for him daily, and even the prison staff seemed to sympathize with him: he was granted unprecedented privileges, and on one occasion was even escorted from prison to visit his newborn daughter at home (Brandt 96-99).

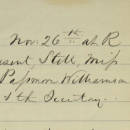

Williamson was defended by the extremely capable legal team of Edward Hopper (son of Isaac Hopper and son-in-law of James and Lucretia Mott) and Charles Gilpen, and his trial stretched on. Meanwhile, it was becoming quite clear that his imprisonment was not aiding the pro-slavery cause. Wheeler withdrew his complaint on November 3, 1855, and Williamson was released from prison.

Case of William Still et al

While Passmore Williamson waited in prison, the other participants in Johnson's escape--William Still and the five black dock-workers--were facing riot and assault charges. John H. Wheeler was still claiming that Jane Johnson had been forcibly abducted, even though she had already submitted an affidavit swearing that she left Wheeler of her own volition. So, now Johnson tried an even bolder approach: she travelled to Philadelphia and personally appeared in court to testify on behalf of the defense.

It was a risky move, for under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act Wheeler could easily conscribe local authorities to recapture Johnson for him. Nonetheless, Johnson appeared as a surprise witness on August 29, 1855. She was escorted to the courtroom by a cadre of female abolitionists: Lucretia Mott, Sarah McKim, Sarah Pugh, and Rebecca Plumly. After giving her testimony, which Mott described as "very clear & satisfact[or]y", Johnson was whisked out the back door of the courtroom by J. Miller McKim. Mott recounted breathlessly: "we didnt drive slow com[in]g. home Miller, an officer--jane & self--another carriage follow[in]g. with 4 officers for protection--and all with the knowledge of the states attorney".

Johnson's surprise appearance had the desired effect. Still was acquitted, the remaining five freedmen were found not guilty of riot charges, and only two freedmen--the two who physically restrained Wheeler--were sentenced for assault. They served just one week's imprisonment. Jane Johnson, meanwhile, deserted her former master in Philadelphia for the second time in two months. She was widely commended for her courage--risking her own freedom to defend the men who had helped her achieve it.

References

Brandt, Nat, and Yanna Kroyt Brandt. In the Shadow of the Civil War: Passmore Williamson and the Rescue of Jane Johnson. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007.

Mott, Lucretia. Letter from Lucretia Mott. 1855-09-04. Mott Manuscripts, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, MSS 035.

Still, William. The Underground Rail Road. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872. 86-97.

Williamson, Passmore. Case of Passmore Williamson. Philadelphia: U. Hunt & son, 1856.