Pennsylvania Hall Association

By Celia Caust-Ellenbogen

Swarthmore College, Class of 2009. Quakers & Slavery Digitization Project Intern

Temple of Free Discussion

In the 1830s, the antislavery movement underwent a dramatic transformation. A rapid influx of non-Quakers coincided with increasing radicalization in some sectors, leading to an ideological divide. There remained the "old guard" of abolitionists, primarily Quaker, who continued to favor petitions and nonviolent protest as the means to attaining gradual emancipation. But now, there also emerged groups of "Immediatist" or "Garrisonian" (after William Lloyd Garrison) abolitionists: they insisted upon immediate and unconditional emancipation, achieved through any means necessary. These latter groups were more outspoken and confrontational about their beliefs, and they invited a corresponding amount of the public's rancor. It became increasingly difficult to secure lecture halls for antislavery speeches, until, in 1837, a frustrated group of Philadelphia abolitionists decided to circumvent the problem by building their own facility.

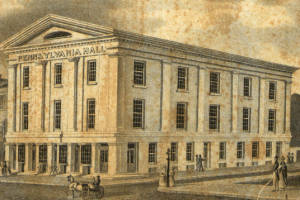

Pennsylvania Hall, as they decided to name it, would be luxuriously appointed with four offices, a small lecture room, two committee rooms, and a large auditorium with three galleries (Brown 127). To cover the $40,000 of building costs, the Board of Managers sold 2,000 shares for $20 each, in cash or trade. Antislavery associations would be free to meet there, but the managers were clear to state the hall would be open to other groups as well. "The building is not to be used for Anti-Slavery purposes alone," the secretary, William Dorsey, announced at the hall's opening. "It will be rented from time to time, in such portions as shall best suit applicants, for any purpose not of an immoral character" (History 6). It was to be, as Daniel Neall Jr. later wrote, "the second Temple of Free Discussion"

Four Days

Pennsylvania Hall was dedicated on May 14, 1838. By May 18, it was not much more than smoke and ash. But in those four short days Pennsylvania Hall enjoyed an illustrious, if all too brief, existence. A long list of distinguished individuals including Arnold Buffum, Lewis C. Gunn, Charles C. Burleigh, and William Lloyd Garrison spoke on the topics of Temperance, Free Speech, Indians, and Anti-Slavery. The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, the Requited Labor [Free Produce] Convention, and the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women all held gatherings within its walls. Daniel Neall Jr. estimated that about 3,000 people attended the events, and described May 16, 1838 as " one of the most satisfactory [nights] of my life". There was unprecedented mixing of racial, gender, and class at Pennsylvania Hall events; as a jury noted in July 1841, "more parade of familiarity between persons of different sexes and colors...than had ever before, or has ever since, been exhibited in the city of Philadelphia" . Aside from general hostility toward abolitionists, it was apparently this racial/sexual mixing that above all infuriated Philadelphians.

Riot

The directors of Pennsylvania Hall were wary of the threat of violence before the doors even opened. Their anxiety understandably intensified when placards began appearing around the city, announcing, "it behooves all citizens, who entertain a proper respect for the right of property, and the preservation of the Constitution of the United States, to interfere, forcibly if they must [at the antislavery conventions to be held at Pennsylvania Hall]" (History 136). When heckling began on May 16 and several windows were smashed, the Executive Committee resolved to seek outside protection. They decided that night, "we cannot undertake to defend the Hall by force--that as law-abiding and peaceable citizens, we throw ourselves upon the justice of our cause, the laws of our country, and the right guaranteed to us by the Constitution".

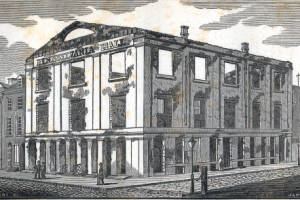

When representatives from the executive committee went to meet with the Mayor, they were hardly comforted by his ambivalent reply: "There are always two sides to a question--public opinion makes mobs and ninety-nine out of a hundred of those with whom I conversed are against you". He told them the only way to protect the hall would be to discontinue the scheduled meetings and give him the keys, which the Board reluctantly agreed to do. On the evening of May 17, the Mayor went to address the anti-abolitionist crowd that was gathered around Pennsylvania Hall. He explained that meetings had ceased and urged the crowd to disperse, but the riot's momentum had already built up. As soon as the Mayor left, the crowd broke down the doors, destroyed the building's contents, and set it aflame. "Flames burst in rolling masses from the windows--soon the whole building was enveloped in one dense, dark coloured, sheet of flame" Daniel Neall Jr. wrote.

As the fire grew, the spectacle drew an even larger crowd of witnesses who may not have actively participated in the riot, but who implicitly approved the violence. 12,000-15,000 were estimated to be present on the scene, but only a small proportion probably actually committed acts of destruction; moreover, no one was ever brought to trial for his role in the events. Firefighters appeared on the scene, but while they prevented the fire from spreading to other buildings, they made no attempt to save Pennsylvania Hall. "The engines made their appearance, but understanding their business, [played] not a drop on the building" Daniel Neall Jr. sardonically observed. By the end of the evening, Pennsylvania Hall was little more than rubble. Still not sated, the mob continued to Thirteenth and Callowhill streets where they attacked the Shelter for Colored Orphans--a charitable institution unconnected with the Anti-Slavery Society.

|

Pennsylvania Hall, before and after the riot, from History of

Pennsylvania Hall (Phila.: Mayhew and Gunn, 1838). This particular copy of

History belonged to Dillwyn

Parrish.

|

|

Legal Struggle

Unfortunately for the subscribers to Pennsylvania Hall, its destruction was only the beginning of a decade of legal and financial struggles still to come. The Board of Directors filed a $100,000 lawsuit against the county for failing to prevent the mob violence. Meanwhile, they allowed the hall's ruins to stand as a tangible reminder of the damages sustained--until, that is, the treasurer Samuel Webb was arrested for the "nuisance" this caused. Webb's arrest occurred in July of 1841, and when a jury soon afterward offered the Board of Directors $33,000 compensation, they decided to take it. The total expenditure on the hall up to that point had been $57,126.39.

Still, even after the Board of Directors agreed to accept the $33,000--one-third their original claim and just over one-half the hall's cost--the award was not forthcoming. They pursued the case to the state supreme court before the county commissioners finally turned over the money, and by that point the amount had been reduced to $27,943.82. In 1848 the Pennsylvania Hall Association finally paid off its debts and interest, and paid stock dividends of $2 dividend per share. Daniel Neall Sr., the president of the association, was dead by the time his son cleared the debts he had incurred on behalf of Pennsylvania Hall.

Legacy

The destruction of Pennsylvania Hall was a watershed event in the history of antislavery activism in Philadelphia. On the one hand, it marks the peak of anti-abolitionist sentiment in Philadelphia; on the other hand, the violence of the event provoked a backlash against precisely such extreme sentiment. While Southern publications rejoiced, the Public Ledger, a mainstream Philadelphia periodical with no abolitionist allegiances, nonetheless declaimed the mob attack on Pennsylvania Hall as a "Scandalous Outrage Against Law and Decency." The May 18, 1838 issue editorialized, "we are decidedly opposed to any mingling of the two races...[but] we should prefer as companions, moral, peaceful and orderly blacks, to profligate and disorderly whites." Daniel Neall Jr. shrewdly observed the attitude shift in a letter to a friend: "The slave has now friends in this City where ears were deaf to the Truth until the fearful encroachments of Wednesday and Thursday nights told them their own liberties were their price to be paid for the Crime of their silence". As Ira V. Brown argues in "Racism and Sexism: The Case of Pennsylvania Hall," the burning of Pennsylvania Hall and other instances of anti-abolitionist violence may have actually had the opposite of their intended effect: they aroused animosity towards anti-abolitionists and won sympathy for abolitionists, and not the other way around.

References

Brown, Ira V. (Ira Vernon), 1922-. "Racism and Sexism: the Case of Pennsylvania Hall." Phylon, the Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture 37:2 (June 1976), 126-136.

History of Pennsylvania Hall, which was Destroyed by a Mob, on the 17th of May, 1838. Philadelphia: Merrihew and Gunn, 1838.

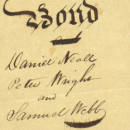

Neall, Daniel, 1817-1894. Daniel Neall Manuscripts, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, SC 086.

Pennsylvania Hall Association. Pennsylvania Hall Association Records, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, RG4/074.