Daniel Neall, Sr.

By Celia Caust-Ellenbogen

Swarthmore College, Class of 2009. Quakers & Slavery Digitization Project Intern

What Will Benefit the Patient?

Daniel Neall was born in 1784 to Jonathan and Sarah Neall, both members of the Society of Friends. Although he grew up in Delaware, a slave-owning state until the Civil War, Neall was more influenced by Quaker testimonies of equality and peace. He was a "disciple" of Warner Mifflin, 1745-1798, an early critic of slaveholding within the Society of Friends, who is credited by Thomas Clarkson as "the first man in America to unconditionally emancipate his slaves" (Whittier 123; Justice 39). In 1810, Neall married Mifflin's daughter Sarah. The couple lived in Delaware, and then in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, before settling in Philadelphia.

Largely self-taught, but eminently gifted, Daniel Neall experimented with many different careers during his life. At times a carriage-maker, a farmer, a watch-repairman, a printer, and an inventor (he received a gold medal from the Franklin Institute at Philadelphia for his patented vertical printing-press), Neall finally settled on dentistry. His talent for extracting teeth was discovered around 1810 by a local doctor, who began referring his patients to Neall for this service. When the doctor died several years later, he bequeathed all his medical instruments to Neall, but it was not until 1828 that Neall began to pursue dentistry in earnest. Over the next 15 years, Neall's innovative techniques, inventions, and improvements, earned him the distinction of "Pioneering American Dentist" (Thorpe). But despite his excellent reputation, Neall never profited much from working as a dentist. As his son, Daniel Neall junior, wrote later, money was a secondary concern: "his first question, and his last being--What will benefit the patient?"

I Shall Do My Duty.

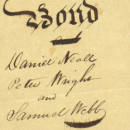

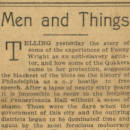

The care and tenderness which Neall demonstrated in treating his patients was yet more apparent in his commitment to social reforms, particularly antislavery. Neall was president of the Pennsylvania Hall Association, a group dedicated to establishing a "Temple of Free Discussion" where antislavery, women's rights, and other reform lecturers could be heard. Just three nights after Pennsylvania Hall was built in 1838, on the night of May 17, the building was surrounded by an angry crowd of anti-abolitionist Philadelphians. According to his friend John Greenleaf Whittier, Neall stood up to the mob and announced, "I am here, the president of this meeting, and I will be torn in pieces before I leave my place at your dictation. Go back to those who sent you. I shall do my duty" (Whittier 123). Despite the protestations of Daniel Neall and other prominent abolitionists present--including Lucretia Mott, John G. Whittier, and Angelina Grimke Weld--Pennsylvania Hall was completely destroyed.

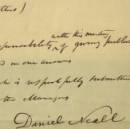

Immediately after its destruction, the Board of Managers of Pennsylvania Hall became embroiled in a legal and financial struggle to recover damages and pay off debts. Daniel Neall remained President of the Association until poor health compelled him to resign in 1845. Still, it was not until 1849--over a decade since the dedication of the Hall, and three years after Daniel Neall senior's death--that his son settled the debts his father had incurred on behalf of the Pennsylvania Hall Association.

Dab of Tar and Homeopathic Dose of Feathers.

In 1840, just two years after the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, Daniel Neall had his second encounter with a crowd of rioting anti-abolitionists. This time, luckily, the only casualty was Neall's coat.

Daniel Neall and his wife were in Delaware, having travelled with her cousin Lucretia Mott on a religious visit. Slaveholders in the area had heard that Mott and her companions were abolitionists, and determined to send them a warning but, unwilling to harm a woman, the angry locals chose Daniel Neall as their target. Extracting the 54-year-old from his host's home, the crowd informed Neall that he would be subjected to tar-and-feathers. Neall calmly agreed to follow them, and the mob, "evidently somewhat nonplussed by the nonchalance of their subject," as Neall's son later wrote, led him away. Neall remained in a good humor as the slaveholders applied a "dab of tar and homeopathic dose of feathers" to his coat, and rode him through town on a rail--adjusting it, however, to seat Neall on the flat side. When they finally released their victim, Neall cheerily announced to his tormenters that any of them were welcome to visit his home in Philadelphia and there receive hospitality. According to Daniel Neall junior, several men availed themselves of his father's offer, and visited the Neall residence to apologize for their unruly behavior.

A True and Brave and Downright Honest Man

Daniel Neall the elder, leaving his legacy in the capable hands of his son, died in Philadelphia on April 15, 1846. He was eulogized by his friend, the great American Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier:

I.

FRIEND of the Slave, and yet the friend of all;

Lover of peace, yet ever foremost when

The need of battling Freedom called for men

To plant the banner on the outer wall;

Gentle and kindly, ever at distress

Melted to more than woman's tenderness,

Yet firm and steadfast, at his duty's post

Fronting the violence of a maddened host,

Like some gray rock from which the waves are tossed!

Knowing his deeds of love, men questioned not

The faith of one whose walk and word were right;

Who tranquilly in Life's great task-field wrought,

And, side by side with evil, scarcely caught

A stain upon his pilgrim garb of white

Prompt to redress another's wrong, his own

Leaving to Time and Truth and Penitence alone.

II.

Such was our friend. Formed on the good old plan,

A true and brave and downright honest man

He blew no trumpet in the market-place,

Nor in the church with hypocritic face

Supplied with cant the lack of Christian grace;

Loathing pretence, he did with cheerful will

What others talked of while their hands were still;

And, while "Lord, Lord!" the pious tyrants cried,

Who, in the poor, their Master crucified,

His daily prayer, far better understood

In acts than words, was simply doing good.

So calm, so constant was his rectitude,

That by his loss alone we know its worth,

And feel how true a man has walked with us on earth.

References

"Daniel Neall, Sr.: Pioneer Dentist, Inventor and Abolitionist" in History of Dental Surgery, vol. 3: Biographies of Pioneer American Dentists and Their Successors, p. 161-166. Editor of vol. 3: Burton Lee Thorpe; series editor, Charles R. Koch. Ft. Wayne, Ind.: National Art Publishing Co., 1910.

Justice, Hilda. Life and Ancestry of Warner Mifflin: Friend--Philanthropist--Patriot. Philadelphia: Ferris & Leach, 1905, 19-20, 38-40.

Neall, Daniel, 1817-1894. Daniel Neall Manuscripts, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, SC 086.

Whittier, John Greenleaf. "Daniel Neall." From The Works of John Greenleaf Whittier, vol. 3: Anti-Slavery Poems, Songs of Labor and Reform, p. 123-124. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1892.